A team of researchers from the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL) at DESY and Uppsala University (Sweden) has developed a new technique to heat water from room temperature to 100,000 degrees Celsius in just 75 femtoseconds (75 millionths of a billionth of a second) to produce an exotic state of water. According to scientists, this setup is the world’s fastest water heater, which can be used to discover peculiar characteristics of water.

“It is certainly not the usual way to boil your water. Normally, when you heat water, the molecules will just be shaken stronger and stronger,” says Carl Caleman from CFEL at DESY.

In the experiment, researchers used the X-ray free-electron laser Linac Coherent Light Source LCLS at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in the U.S. to shoot intense and ultra-short flashes of X-rays at a jet of water.

“Our heating is fundamentally different. The energetic X-rays punch electrons out of the water molecules, thereby destroying the balance of electric charges. So, suddenly the atoms feel a strong repulsive force and start to move violently.”

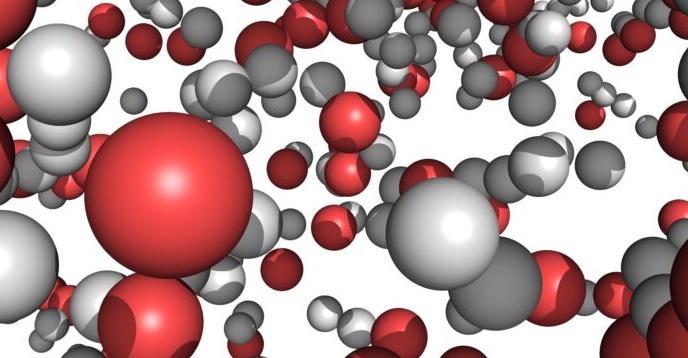

The experiment showed that there were almost no changes in the structure of water molecules up to 25 femtoseconds when the X-ray pulse started to hit water molecules. At 50 femtoseconds, molecules started shedding electrons and turning to plasma. At 75 femtoseconds, most water molecules had split into hydrogen and oxygen.

“In less than 75 femtoseconds, the water goes through a phase transition from liquid to plasma. A plasma is a state of matter where the electrons have been removed from the atoms, leading to a sort of electrically charged gas.”

“The energetic X-rays punch electrons out of the water molecules, thereby destroying the balance of electric charges.”

“So, suddenly the atoms feel a strong repulsive force and start to move violently.”

According to co-author Olof Jönsson from Uppsala University, when water transforms its state, its new state shows similar characteristics as some plasmas in the sun and the gas giant Jupiter. However, it still remains at the density of liquid water, and is hotter than Earth’s core.

Scientists commonly use X-ray diffraction technique to investigate the structure of crystals and other solids, but this new experiment shows that this approach needs to be altered when applied to liquids.

“It is important for any experiment involving liquids at X-ray lasers. In fact, any sample that you put into the X-ray beam will be destroyed in the way that we observed. If you analyze anything that is not a crystal, you have to consider this,” said co-author Kenneth Beyerlein from the CFEL in Hamburg, Germany.

“If you analyze anything that is not a crystal, you have to consider this.”

Co-author Nicusor Timneanu from Uppsala University, said, “The study gives us a better understanding of what we do to different samples.”

“Its observations are also important to consider for the development of techniques to image single molecules or other tiny particles with X-ray lasers.”

The detailed findings of the study were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.